And it won’t be pretty. We have collectively learned nothing from Hitler’s rise to power. And it is just happening all over again, through the same institutions that we thought were set up to resist the next fascist takeover.

Background

History has a way of repeating itself, especially when we fail to learn from the past. The rise of fascism in the 20th century, epitomised by figures like Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, was not an isolated incident but the result of specific social, economic, and political conditions that have emerged repeatedly throughout history. Today, as we face similar challenges, it is clear that the lessons of the past are once again being ignored.

The cyclical nature of history is evident in the way societies, when confronted with crisis and uncertainty, often turn to authoritarian solutions, seeking strong leaders who promise to restore order and national pride at the cost of democracy and human rights. This cycle has been observed across different eras and regions, from the fall of the Roman Republic to the rise of fascist regimes in the 20th century, and now, we are witnessing its resurgence in the 21st century.

In this context, the rise of fascism today can be seen not as a sudden anomaly but as the latest iteration of a recurring historical pattern.

The financial crisis of 2007 sent the world’s entire economy into recession, and would be the catalyst of many beautiful citizen protest movements, like Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, the 15-M, the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, and the 2010 United Kingdom student protests, among others.

People suffered for years under strict austerity measures to stabilise the economy after a collapse of subprime mortgages erased between 2 and 10 trillion USD, depending on the estimation, in the global financial system, and most western countries contracted their GDP around 5% due to the crisis.

During the 2010, it seemed like there would be change. Protestors went home, but there was no comprehensive policy change. However, life continued as normal. Economies would slowly start to recover, and get back on track of GDP growth.

Then it happened again, another crisis: First, a few cases of pneumonia in China. Then it spread, over days, and weeks. Alarms were being raised, people were being hospitalised, nobody knew what was happening, and soon enough, a pandemic was declared. Most countries enforced strict quarantine measures including mouth coverings and curfews that turned many people unemployed: baristas, office services, real estate agents, millions of people lost their jobs, while office workers were being told to go home, and work from home for a few weeks, which turned into months, and for some, became permanent.

During COVID, conspiracy theorists ran rampant through social media platforms, spreading disinformation involving Bill Gates, George Soros, the World Health Organisation, the US, the EU, the World Economic Forum, and more.

Current times

It is hard to point to a single specific event causing a rise in fascist sentiment, but the world has changed drastically in the last 10 years, and some of the progress that was achieved has stopped, and, in some cases, started to reverse.

Anti-immigration and anti-refugee sentiment

Although Europe has traditionally been one of the most open and welcoming regions, it is starting to turn its back on immigrants and refugees.

The most significant turning point came with the 2015 refugee crisis, when over a million refugees and migrants, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, arrived in Europe. Initially, some countries, particularly Germany, were welcoming. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s “Wir schaffen das” (“We can do this”) approach was emblematic of this initial response. However, as the numbers swelled, the political and social backlash grew.

The scale of the crisis, combined with later terrorist attacks across Europe, and resulting protests made European politics less welcoming of immigrants, and more in favour of border controls.

Countries around Europe have also used immigration as a political tool, some notable examples:

In 2015, there was a sharp increase in migrants arriving in Lapland, in the Finnish-Swedish border. In parallel, there was an increase in the number of migrants at two Finnish-Russian border crossing points. In 2016, Norway stopped to consider asylum applications from migrants with Russian residence documents. Source [Archived version]

In February 2020, Turkey announced that it would no longer stop refugees from attempting to cross into Europe, leading to a significant increase in migrants trying to enter Greece. This was widely seen as a tactic to pressure the EU for more support in Turkey’s conflict with Syria.

In August 2021, Belarus was accused of orchestrating a migrant crisis along its borders with Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia.

In August 2021, a similar situation developed in the Morocco-Spain border around Ceuta and Melilla, whereby Morocco relaxed border checks, and allowed thousands of migrants to cross into Ceuta. This was interpreted as retaliation for Spain’s decision to provide medical treatment to a political figure that opposes Morocco’s territorial claims. Morocco is also known to periodically leverage the threat of migration to negotiate better deals with the EU.

The growing hostility towards immigrants and refugees is not just a response to external crises but a symptom of a deeper shift towards authoritarianism, where fear and exclusion are used to consolidate power.

Terrorism

During 2015 and 2016, several terrorist attacks took place in France, Belgium, and Germany. This shocked the world and would steer these territories into less favourable migration policies, with parties like AfD taking a strong anti-migration stance during 2015 which significantly boosted its popularity.

Populism and the erosion of truth, the slow-boiling frog

The boiling frog apologue is a powerful metaphor for the current state of world politics. Just as a frog in slowly heating water fails to perceive the danger until it’s too late, societies today are being gradually desensitised to extremist rhetoric, making previously unthinkable ideas appear almost logical.

Populism, as both a political strategy and a movement, is rooted in the notion of representing “the people” against “the elite.” This dichotomy is a hallmark of populist rhetoric, where leaders claim to be the voice of the “ordinary people” while vilifying the establishment. Historically, populism has appeared in various forms across the political spectrum, from left-wing movements like those led by Latin American leaders to right-wing movements in Europe and the United States.

Populism’s historical lineage can be traced back to the 19th century, notably with the People’s Party in the United States. However, modern populism has taken on new dimensions, often aligning with nationalism and anti-immigration stances. The relevance of populism today lies in its ability to exploit societal divisions and fears, creating an environment where democratic principles are undermined.

Populist leaders and movements can serve as a precursor to fascism by exploiting people’s fears, promoting nationalism, and attacking democratic principles.

The rhetoric of “us vs. them” employed by populist leaders enables these parties and movements to justify hatred and disrespect towards minorities, who are scapegoated for society’s problems. This divisive strategy not only polarises societies but also erodes the social fabric by turning different groups against one another.

The most notorious populist figure in recent history is Donald Trump. Running on a platform of “America First”, he won the election that would make him the 45th president of the United States. His brand of populism combined nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric with attacks on established institutions and the media.

Other relevant figures include Viktor Orbán and Jair Bolsonaro, who have similar positions to Donald Trump including xenophobic values, conservatism, criticism towards environmental regulations, and the support of traditional national values over immigration and foreign influence.

However, while populism seems to be having a greater effect on right-wing voters at the moment, populism is not a characteristic of right-wing politics, and there are cases of left-wing politicians effectively using populism to drive their agendas.

Right-wing populist figures capitalise on free speech to make controversial statements, framing them as bold truths that others are too afraid to voice. They focus on telling people what they want to hear, without providing clear, actionable plans on how they will achieve their promised goals. This lack of transparency and practical solutions allows them to maintain broad appeal while avoiding scrutiny over the feasibility of their policies.

This is the intersection between populism and free speech. I talk more about free speech in my previous post: Free speech is not a noble goal to pursue. Populists often weaponise free speech to normalise xenophobic discourse. Through the illusory truth effect, repeated false claims can become more believable, leading to widespread misinformation.

Moreover, populist leaders are quick to dismiss established media as “fake news,” promoting confusion among the public, who may then struggle to distinguish between truth and falsehood. This erosion of trust in traditional sources of information is another dangerous consequence of modern populism.

The overton window is moving to the right

The overton window is a concept to name what the currently sociopolitically acceptable range of policies exist. Political actors have skillfully manipulated the Overton window, gradually shifting what is considered acceptable discourse to include more extreme right-wing ideologies, and because of the above mentioned circumstances, it is slowly but surely moving to the right.

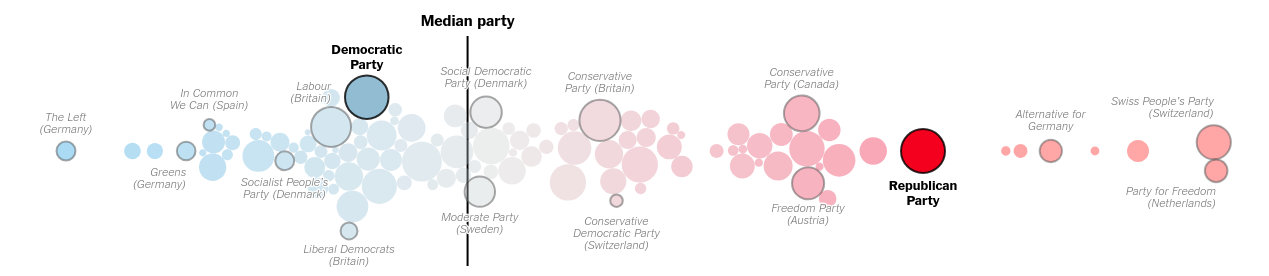

Sahil Chinoy writes: What Happened to America’s Political Center of Gravity? [archived version], on how there seems to be a very clear trend to the right worldwide. Even though the title mentions America, the included chart is very illustrative of current world politics:

According to the chart, the vast majority of parties represent right-wing and center-right ideologies, and are much further from the center than even the most extreme left-wing parties. And for the left side, the majority of left-wing parties remain very close to the center, and only a handful of them dare to go far into the left spectrum.

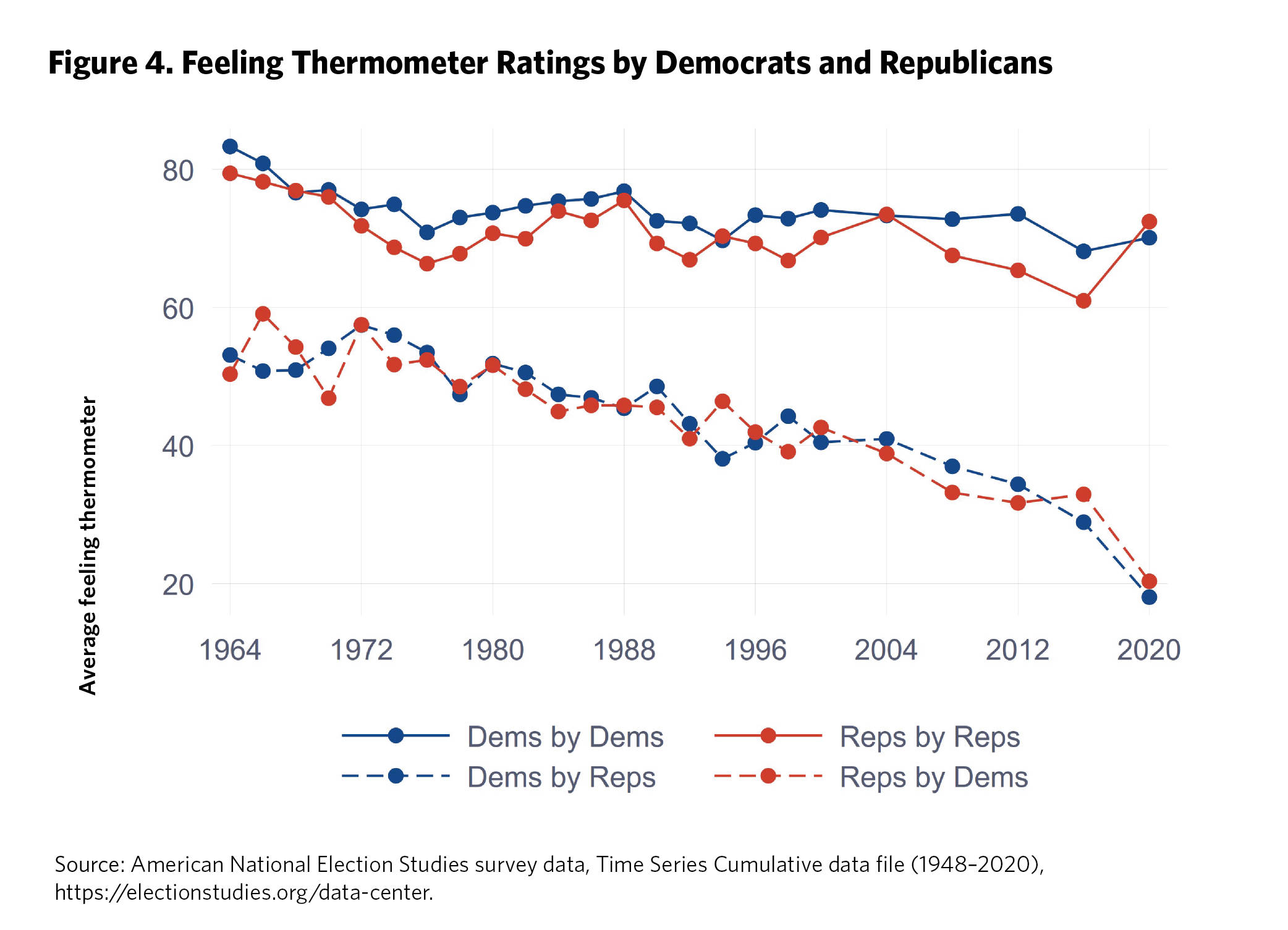

Rachel Kleinfeld published a paper on Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says [archived version] [PDF version]. And I would like to take a look at two charts:

In the above chart, we can clearly see how, even though Democrats and Republicans trust their own peers slightly less in 2020 compared to 1964, we can also see that both parties’ trust in their respective opposition has tanked, and in 2020 they were at alarmingly low levels. This means Republicans nowadays consider themselves politically far away from Democrats, and vice-versa, and this contributes to further polarisation, populism, and radicalisation, and makes passing laws much harder and require more compromises on both parts.

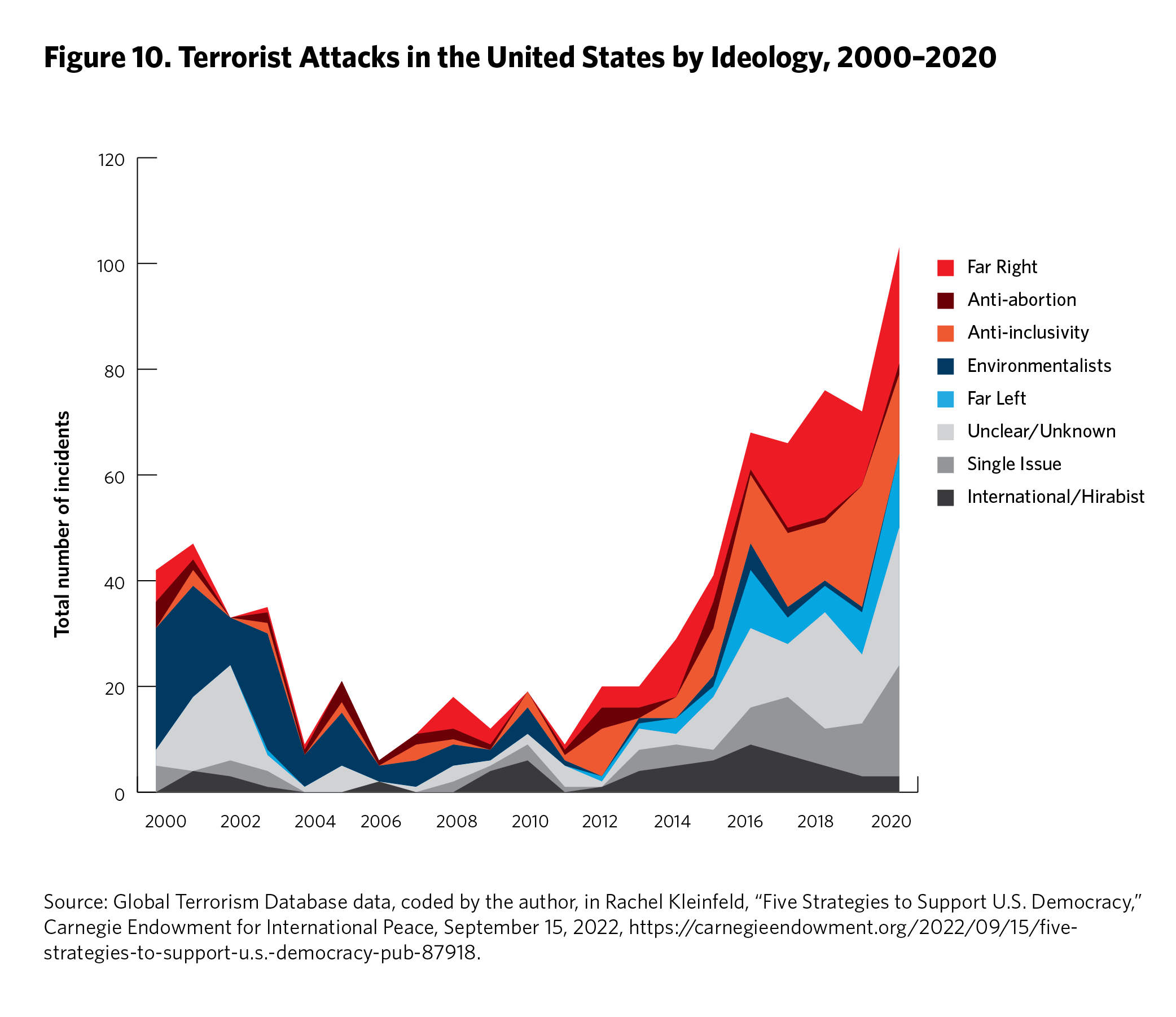

In the same article, we find a chart illustrating terrorist attacks in the US over the past few years:

Not only attacks have gone up massively, but we see a significant rise in attacks determined to be far-right and anti-inclusivity, although environmentalist terrorism has been mostly replaced by far-left terrorism, but still represents a lower share compared to right-wing groups.

United States

The Trump administration’s “Muslim ban,” which restricted travel from several predominantly Muslim countries, was initially met with widespread condemnation. However, it eventually gained significant support among right-wing circles.

In 2022, The United States Supreme Court decided to overturn Roe v. Wade, undoing 50 years of reproductive rights.

Hungary

Viktor Orbán in Hungary has pushed for policies that were once deemed far-right, such as anti-immigrant measures and restrictions on press freedom, with growing acceptance. Orbán’s rhetoric around “protecting European Christian values” against migrants has moved from fringe discourse to being a cornerstone of his government’s policy, further exemplifying this shift.

Denmark

Certain areas were labeled “ghettos” and stricter laws were enforced on residents, such as mandatory preschool for children from immigrant backgrounds to “integrate” them into Danish society. This reflects a move towards more hardline policies on immigration and assimilation that were previously considered too extreme.

United Kingdom

While UK has never been particularly fond of the European Union, and they never adopted the euro or became part of the Schengen passport-free area, Brexit, largely driven by concerns over national sovereignty and immigration, was initially a fringe position. However, the Brexit movement would eventually culminate in the United Kingdom starting the process to leave the European Union.

Conclusion

We live in an extraordinarily difficult situation of mass disinformation campaigns, polarisation and social justice.

War has returned to Europe with the illegal invasion of Ukraine by Russia that started in 2022, after more than 70 years of relative peace in Europe, to the West of Russia, and more than 30 years after the end of the Cold War. The conflict between China and Taiwan has been brewing over the past few years, and every few months, some US military intelligence warns us that we are closer to a war in Taiwan than we think, yet the world moves on.

Israel invaded Gaza in 2023, and is upsetting all arab countries, including Iran. Meanwhile the United States continues to express support for Israel’s military objectives.

Economic fears abound, and a certain famous CEO has purchased one of the world’s most important social networks only to spread ridiculous far-right conspiracy theories, seeding people’s lives with fear and doubt.

When Hitler was defeated, we all thought that it was over. We put measures in place to make sure nothing like this ever repeats. Technical measures like minimum vote percentages in many democratic countries, minimum country thresholds in the EU, the illegalisation of nazi symbology and parties representing far-right ideologies, national espionage campaigns to disarm far-right terrorist cells before they can cause any harm, and many other strategies to try to ensure Hitler wouldn’t repeat.

But it is coming back to haunt us. The problem is democracy is inherently fragile, as, during periods of hardship, people want and need solutions fast. And someone can come at any time, and tell them exactly what they want to hear: we will lower taxes, we will increase employment. Everyone will be rich, it’s the immigrants who are the problem, so we will kick them all and we will once again be powerful and prosperous.

But it’s not so simple. Nothing is ever so simple. I can only hope we turn back before it’s too late.