Most of the modern West is built around the idea of meritocracy. Because of how influential Christianism has been in Europe, and later America, this can be traced back to Abrahamic traditions. Many societies nowadays revolve around “hardened individuals”, “self-made men”, and individual financial success. Admittedly, this behaviour motivates people to give their best, as you condition them to believe their efforts have a measurable impact on their future life, by which more effort translates into a better, more comfortable life. And for sure, there’s a component of effort and hard work in everyone’s future.

Ulveon’s note: I started writing this post way before the US elections. My posts usually take several months to finish, and I didn’t expect any of what’s happening in the USA right now. With “merit-based hiring”, the relentless attacks on DEI and more, the USA has embarked on a dark and sinister journey of increased exploitation, discrimination, and worship of the US dollar to drive a specific political agenda.

But, to what degree does personal effort influence your future? The answer varies significantly depending on the kind of effort and the discipline to which it is applied.

Nowadays, most modern meritocracy advocates have stopped using the “hard work” cliché, as the usual criticism of this is how hard warehouse workers work compared to the average white-collar office worker. The preferred term now is “working smart”, implying that it’s not about unfocused hard work but about very methodical work in specific areas yielding a significant impact. That’s to say, it’s less about physical effort or the number of hours and more about results.

Luck

For many, this is a sensitive and emotional topic. Telling someone that effort doesn’t matter and that success is a matter of luck would imply that investing effort into a task is a waste of time. Conversely, for many wealthy individuals, it becomes difficult to justify their wealth ethically.

In my opinion, the following video by Veritasium explains the factor of luck very well.

A recent study has shown how luck plays an ever-increasing role in a person’s success. Naturally, it’s not all luck: high levels of effort might be the determining factor for better outcomes in groups with similar levels of “luck”.

When I refer to “luck”, I mean various conditions and situations beyond an individual’s control. These factors include parental wealth, genetic predispositions to illnesses such as asthma or mental health issues, personality traits, living conditions, the number of siblings one has, and connections with powerful and influential people, among others.

Most famously, this evidence is supported in “Talent vs Luck: the role of randomness in success and failure” by A. Pluchino, A. E. Biondo & A. Rapisarda [mirrored PDF].

James Clear argues [archived version] that “Absolute Success is Luck. Relative Success is Hard Work.”. Indeed, I agree. Not all is luck. If you are lucky but don’t work for it, you might inherit wealth but will also easily lose it. Conversely, if you work hard, as unlucky as you might be, you can land yourself in a better position than you would otherwise might have.

The fact remains that there’s an invisible “glass ceiling” for every individual, shaped by factors such as their birthplace, upbringing, parental wealth, or how many siblings they have.

There are diminishing returns to hard work. I firmly believe random people cannot become wealthy like Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs, or Bill Gates, regardless of the effort they put into their careers or aspirations. It takes not only a specific type of psyche and work ethic but also a specific set of circumstances and the ability to see these patterns unfold before you and act on them to seize the opportunity. Additionally, it necessitates a certain level of ruthlessness and a loose ethical code, but I will discuss that in another post.

Merit

How do we measure merit? Nobody has an exact answer. While number of worked hours is a good approximation, instead, many proponents of meritocracy assume wealth equates to merit and try to reason through how rich people deserve their wealth. This reverses the implication by which people with high salaries are also high-effort individuals.

Indeed, you can find reasons for rich people deserve their wealth. They may have invented something revolutionary or groundbreaking at some point. They may work long hours or be charismatic and attract the best talent because they have qualities that allow them to evaluate exceptional individuals quickly. But if the implication was like this, it would also imply there are no rich people who are lazy and unachieving.

Many of today’s billionaires have experimented and failed repeatedly dozens or hundreds of times before discovering the formula for success. Success rarely materialises effortlessly; it is equally easy to see how individuals with greater financial capital and resources can engage in such iterative experiments. In contrast, for someone with fewer resources, failing might mean bankruptcy or even losing their life savings. Failure is common, yet success stories outnumber setbacks in public discourse. In other words: more money gives you more opportunities, making success statistically likely compared to less wealthy individuals.

Success

Success is frequently described as the favourable outcome of an endeavour, and it’s somewhat perverse, as we measure merit based on success. Naturally, failing is easy, but succeeding is not. Experiencing failure may not yield significant outcomes, whereas achieving success has the potential to result in transformative scientific breakthroughs or pioneering advancements in consumer products.

This can also create a culture where fear of failure is rampant, and prevent people from even trying.

Systemic inequalities - Compounded privilege

Meritocracy is oftentimes seen as a zero-sum game where the winner takes all. This perspective can reinforce existing privileges because wealth tends to be passed down through family connections. Wealthy individuals can easily finance their children’s education, giving them more significant opportunities to become well-educated adults. As a result, they are more likely to build valuable connections and secure well-paying jobs than less privileged individuals with limited or no access to higher education. In some cases, like the United States, education is not all about learning, but about connections. Attending MIT might be an excellent investment primarily because MIT students tend to be wealthy and successful. Proximity to them can prove beneficial if you are interested in founding a startup.

This creates a compounded privilege scenario wherein the children of the affluent inherently possess greater advantages than their less-privileged counterparts, thereby further increasing the gap between the wealthy and the impoverished and undermining any aspirational meritocratic ideals.

Perverse capitalist incentives

People need to pay their bills. To achieve this, individuals must maintain employment or possess alternative sources of funding. It would be ideal for students to receive financial support from their parents while pursuing their university studies, alleviating concerns related to income or educational expenses. Unfortunately, this is not always the case; some individuals may have parents with limited financial resources or may be otherwise unable to depend on their parents for assistance.

In cases like these, it effectively means that poor people have to work and study simultaneously if their parents can’t afford to educate them. It adds stress to one’s life and makes success much less likely, but the choice is limited: They can either study and work, or only work. Dedicating oneself to studying exclusively is not feasible in most countries, because, regardless of tuition, students need a place to live, for which they have to pay.

Psychological and social factors: fallacies

People may endorse meritocracy to rationalise the cognitive dissonance coming from social inequality.

Cognitive dissonance reduction

Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals experience psychological discomfort when holding contradictory beliefs or when their beliefs conflict with observed reality. In the context of social inequality, disadvantaged individuals may experience dissonance between their disadvantaged position and their belief in a fair society. To reduce this dissonance, they may embrace meritocratic beliefs, convincing themselves that the system is fair and their position is a result of personal decisions rather than systemic issues or factors outside of their control.

Social identity and status

Humans are social by nature. And because of this, they will seek to belong to groups. Nobody actively seeks to belong to a group of lazy, unachieving individuals, but people in highly competitive societies often make it part of their personality to humblebrag about how hard they work, or how many hours they dedicate to working. The implication is that, not only are they virtuous for working hard, but they’re also wealthy because of this.

Proportionality

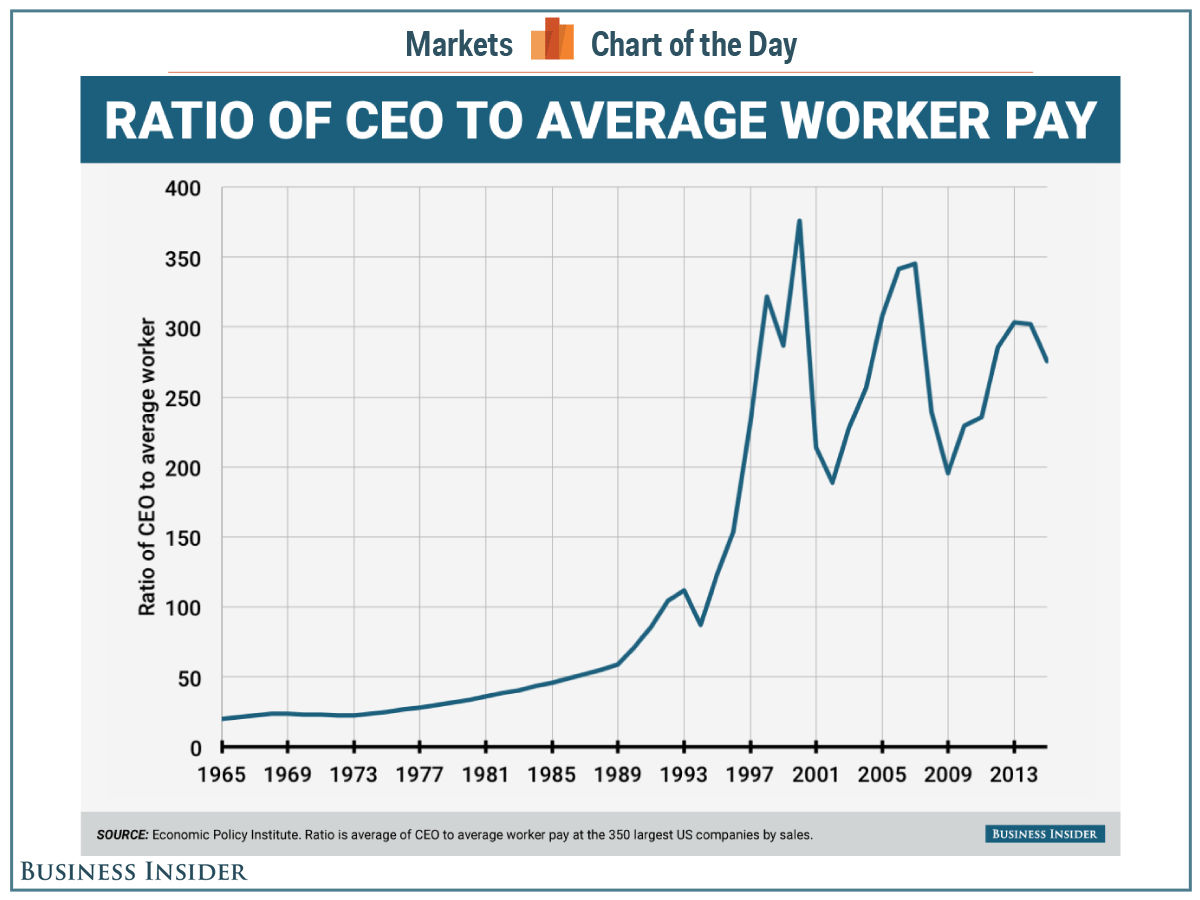

According to meritocracy, people working 10x as hard (or 10x as smart) as others should also benefit from increased income; possibly 10x as much, or maybe more than that. Consider: CEO-to-worker compensation ratios stood at slightly below 400x in 2021. Does the average CEO work 400x as hard as the average employee?

Intergenerational earnings elasticity

This is a fundamental concept to understand. As a mathematical formula, IGEE (Intergenerational Earnings Elasticity) is:

$$\log(Y_{child}) = \alpha + \beta \log(Y_{parent}) + \epsilon$$

Where:

- $Y_{child}$ is the child’s adult earnings

- $Y_{parent}$ is the parent’s earnings

- $\alpha$ is the intercept term

- $\beta$ is the intergenerational earnings elasticity

- $\epsilon$ is the error term and represents all other influences on the child’s earnings that are not explained by parental earnings

The value of $\beta$ represents the fraction of income that is, on average, transmitted across generations. For example:

- An IGEE of 0.4 means that if a parent’s income is 100% above the average in their generation, their child’s income is expected to be 40% above the average in the child’s generation.

- An IGEE of 0 indicates complete mobility (no relationship between parent and child earnings).

- An IGEE of 1 represents complete immobility (the parent’s relative earnings position is fully passed on to the child).

Intergenerational Earnings Elasticity is an application of the Intergenerational Elasticity formula (IGE), which represents a crucial measure in understanding the persistence of advantages or disadvantages across generations. Its importance can be explained in several key aspects:

- It helps drive policies promoting intergenerational mobility and identify mechanisms of persistence

- Evidence suggests increased levels of IGE not only drives innovation, but may also contribute to economic growth

- Increased economic efficiency - by preventing nepotism and ensuring everyone has similar opportunities

- Social justice

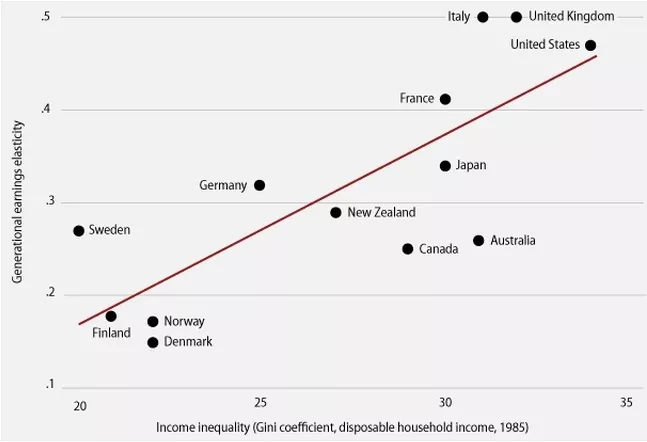

The Great Gatsby Curve

The curve demonstrates a positive correlation between income inequality and intergenerational earnings persistence.

Alan Krueger, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, coined this term. The curve suggests that countries with high inequality may offer less economic opportunity for upward mobility, a central theme to American culture and politics: the “self-made man” or “pull yourself up from the bootstraps”.

There are several reasons to explain the mechanisms behind the Great Gatsby Curve:

- Family investments: Wealthy parents can invest more in their children’s education and development by sending them to luxurious private education centres.

- Social influences: Networks and connections play a significant role in every individual’s economic success. Individuals from high-income backgrounds are often more socially desirable, reinforcing this dynamic.

- Lobbying and politics: Inequality can lead to unfair influence by think tanks run by wealthy people, who can influence and direct economic policies that, in turn, favour them.

The Great Gatsby Curve is supported by research like:

- “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States” by Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline & Emmanuel Saez [mirrored PDF]

- “The Great Gatsby Curve” by Steven N. Durlauf, Andros Kourtellos, and Chih Ming Tan [mirrored PDF]

- “The dynamics of the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’ and a look at the curve during the Great Gatsby era” by Diego Battiston, Stephan Maurer, Andrei Potlogea & José V. Rodríguez Mora [mirrored PDF]

Social mobility

The proponents of meritocracy may be inclined to believe that increased regulations and socialism is a deterrent for social mobility, as it might create “leeches” and lazy people who depend on government welfare; but studies show social mobility does not correlate with less socialism and less regulations.

On the contrary, a report by the Social Mobility Commission of the United Kingdom [mirrored PDF] highlights:

- Investing in inclusive, high-quality education can stimulate innovation-led growth and increase social mobility.

- The geographic concentration of innovative firms in the UK limits opportunities for many workers, where cities like London are highly sought after, but other British regions lose high-skilled workers, which in turn causes innovative firms to leave these regions, further reinforcing this feedback loop.

- Improving supervision of practices that hinder competition and reducing barriers for new businesses can significantly enhance the success of new market entrants and benefit the surrounding community.

All these measures are fairly interventionist, and I’m sure many libertarians are shocked by the mere suggestion that increased government oversight can lead to prosperity.

Conclusion

Meritocracy is not real. It’s a nice idea in principle, and it ties back to my post on the implicit social contract: Those who contribute the most to society are rewarded proportionally. On the contrary, those deemed to be contributing the least, or even taking from the rest of society without contributing (as is the case in chronically ill patients, the elderly, the unemployed, and so on), are pushed away from society and resigned to poor living conditions, food insecurity, and more.

Again, the problem is that meritocracy doesn’t exist. It is not possible to rank humans according to how much they contribute to society. Even approximations like income fail miserably when CEOs play financial gambles to increase revenue without improving the quality or price of the products offered or their employees’ living and working conditions.